CINQUE per MILLE

Help us with our projects. Give your 5x1000 to our FOUNDATION. C.F. 84005130483

CINQUE per MILLE

Help us with our projects. Give your 5x1000 to our FOUNDATION. C.F. 84005130483

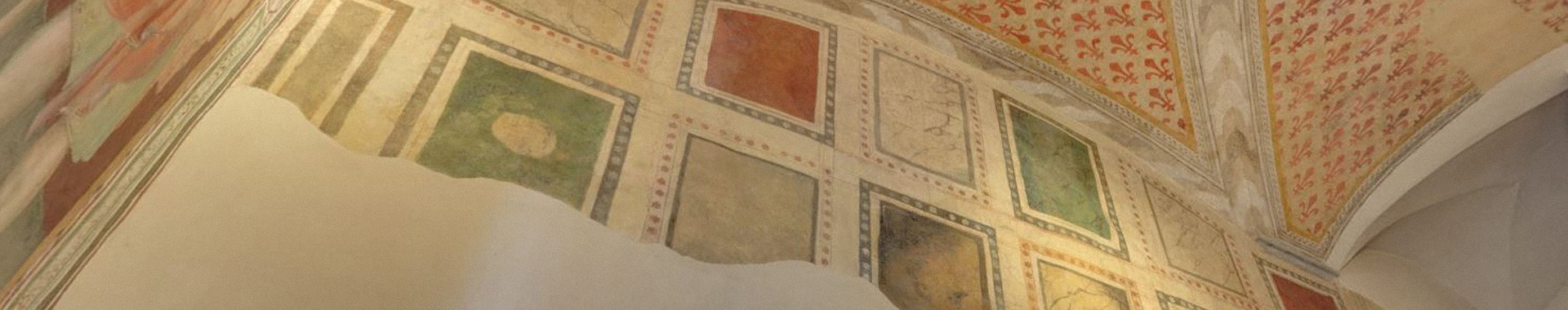

The splendid ground floor room with two beds (now also called the Stork bedroom), with vault decorated with lilies and walls and a luxuriant garden populated by birds, was destined for guests to the Datini home.

The original floor, still preserved today, is made of lime mortar and crushed bricks.

The room is dedicated to Francesco and his wife Margherita, who married in 1376 in Avignon.

On display is an original letter from Margherita, testifying to the copious correspondence that took place between the couple during Francesco’s long periods away from home dealing with his business affairs. It is also possible to admire a XIV century Islamic copper alloy bowl.

A fireplace complete with firedogs, fork, shovel and tongs, warmed the room, while lighting was provided by brass candlesticks. The furnishings consisted of two beds with painted curtains and predella, canopy, mattress, a carpet, a wardrobe, a folding chair, a large church bench, another bench, a walnut table with two stools and two little tables; one with a chessboard, the other with a board for playing noughts and crosses. There were also a painted desco da parto (birth tray) – for serving delicacies to the woman who had just given birth -, sheets and pillow-cases, some of which bearing Francesco’s coat of arms, a painting of the Virgin and Jesus Christ on wood and another depicting the Trinity.

In September 1391 two Florentine painters arrived in Prato, Bartolomeo di Bertozzo and his companion Agnolo (for a long time erroneously identified as Agnolo di Taddeo Gaddi) who flanked Niccolò Gerini in decorating the palazzo.

The most important work undertaken by the two painters was the decoration of the so-called room with two beds. Regarding this commission, documents recount: “la volta della chamera dipinta a gigli gialli nel champo azuro, con li conpassi dipinti armi in tutto cho rrìgoglio [...] le mura di detta chamera, intorno dipinta ad alberi e panchali [...] ghuancie di due fìnsestre di deta chamera [... ] el palcho di detta chamera, dipinto con conpasi e rose”.

The room still today preserves the wall decoration described above: the lilies on the vault, like the writing desk, have lost their yellow colouring and the colours of the Bandini coat of arms, again in this case, have deteriorated; the remaining items, the part of the decoration that masquerades as a drape, acting as back-rest , against which benches were probably placed – and the walls – on which a garden with fruit trees and birds are depicted – can still today be seen in all their splendour. In particular, the lower Part of the wall appears as though covered with tiles bearing the Datini coat of arms and another emblem that is difficult to distinguish due to the rough surface and peeling paint.

In medieval houses, a false cloth decoration was generally accompanied by the description of a garden which, in the upper register, consisted of trees placed at regular intervals, with rounded crowns, laden with fruit, and surrounded by colourful birds on the wing. Obviously there were many variations to this general rule. In Palazzo Datini landscapes followed a different sequence: instead of occupying a small portion of the wall and framed by arches, the trees are depicted in continuous succession over three-quarters of the four walls and are seen in their entirety (from the ground to the top of their crown).

According to some scholars, the particular interpretation given to the Prato motif is perhaps explained by the merchant’s contact with French reality and in particular, that of Avignon (in the Torre della Guarda Roba in Palazzo dei Papi, around 1340, a group of Italian artists painted a series of authentic landscapes devoid of all structural architectonic framework).

Aside from reasoning over Palazzo Datini’s possible sources, the success of the decorative tree motif can be interpreted as a possible reflection of the growing importance assumed by gardens in the fourteenth century as a complement to the house and a status symbol of the new up-and-coming class, an importance reiterated also in the specific case of Prato by the substantial expenses sustained by the merchant in creating his own garden.